Revolution beyond the Boundary: Sir Hilary Beckles Unveils Frank Worrell’s Fight Against Colonialism in Cricket

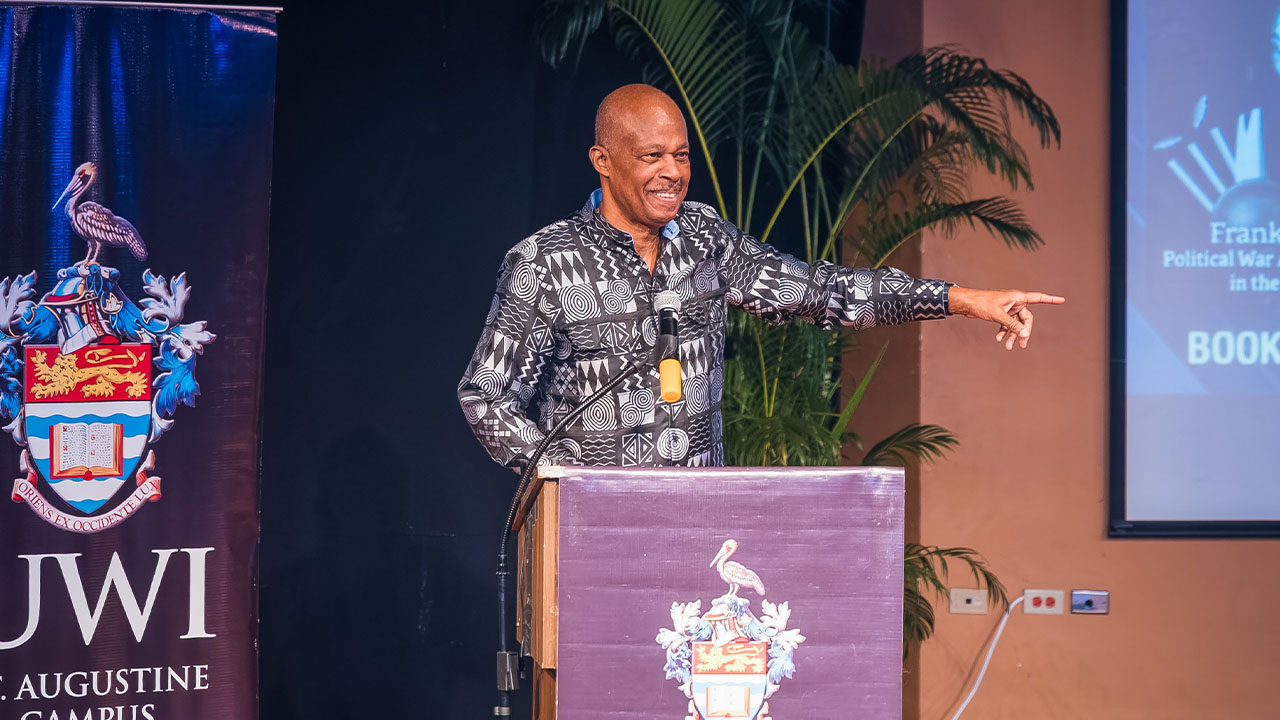

A captivating and robust discussion unfolded at the launch of Professor Sir Hilary Beckles’ latest book, Cricket’s First Revolutionary: Frank Worrell’s Political War Against Colonialism in the West Indies. The event, held on October 21 at The UWI St. Augustine, was under the patronage of Pro Vice-Chancellor and Campus Principal, Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine and was expertly chaired by Dr. Indira Rampersad, Head of the Department of Political Science.

It featured three reviews of the book, starting with the Chair, followed by the distinguished intellectual, Professor Selwyn Cudjoe, ORTT, Academic, Historian, and Editor, and culminating with Dr. Roy McCree, the newly appointed Dean of the UWI’s Faculty of Sport.

To let off a little steam, there was a musical rendition of Black Stalin’s classic song “Bun Dem”—the author’s choice—performed by Mr Kevan Calliste (Stalin’s grandson) and accompanied by Mr Josiah Lewis. There was a skilful, soothing reading of three selected passages by Dr. Justice Anthony DJ Gafoor, Chairman of the Tax Appeal Board of Trinidad and Tobago. These were followed by a spirited response by the author who thanked the reviewers for their delightful provocations. The evening closed with a dance interpretation of Bob Marley’s “One Love” by La Shaun Prescott.

Dr Rampersad set the tone for the launch event by focusing on the author’s use of the “subaltern studies” analytical methodology, pioneered by Indian literary scholar Gayatri Spivak, which captured the role of the working people in India’s struggle against colonialism. She commended Sir Hilary for integrating political and conceptual understandings within the scholarship of West Indian and East Indian historians.

The book is labelled a “political history” of Sir Frank. Sir Hilary is explicit that it is first and foremost a contribution to West Indian politics and history. It is about black and brown people who fought and died for political federation and national independence. It is about the anti-colonial consciousness and strategies of “Worrell the Warrior”, who set out as a school boy and cricket protege to criticise, discredit and destroy the white supremacy system in society and its cricket culture.

According to Sir Hilary, Worrell was a close activist comrade to the radical political leaders and intellectuals of the 1950s and 1960s, and was branded a “revolutionary” by the global media. He was conscious of the labels, “Black Bolshevik” and “Black Panther”. There was a steely determination to turn the West Indian political world upside down, consolidate the social justice democracy movement, and create an irreversible new cricket world. These he achieved, hence the description “Cricket Revolutionary”.

Worrell, he said, set out to win the hearts and minds of the West Indian masses to achieve the grand objective. He saw them as agents of their own history and knew they would act in their self-interest. He knew this long before CLR James joined the campaign in 1959, following the spectators’ revolt at Queens Park Oval. “Worrellitis” was the term in widespread usage long before the rebellion against the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB), and Sir Errol Dos Santos, its authoritarian president, had taken place.

While James was brilliantly writing and speaking, Worrell was strategically acting. Critically, while James harassed the WICB, Worrell was the harbinger of the victory on the ground.

The two men eventually split in the most unpleasant public fashion. In 1962, James led a public campaign to have Worrell removed as team leader, insisting he should not lead the team on the 1963 tour of England. Worrell ignored this call and led the team to a great victory, after which he retired and passed the baton to Garry Sobers, the working-class “subaltern” from inner-city Bridgetown.

It was this “ghetto youth” who led the West Indies to the top of the cricket world, validating Frank Worrell’s vision. James, noted Sir Hilary, never publicly admitted that he was wrong, and merely carried on as if his anti-Worrell broadcast did not matter.

In his review, Professor Cudjoe expressed that he was not comfortable with Sir Hilary seeking to minimise James’ hegemonic role in finally winning official support for Worrell’s captaincy. Sir Hilary responded by showing how Worrell had launched his campaign in 1948, and after a long and bitter decade of struggle, his control role was marginalised by James’ own account of events.

Dr McCree focused on the author’s strategy to deconstruct James’ analysis by highlighting the timelines and factual details of Worrell’s war to undo white supremacy and replace it with a multi-racial democracy.

The conversation was sizzling. So too is the book, says Dr Rampersad.

Cricket’s First Revolutionary is available locally from Metropolitan Book Suppliers Ltd and online via Ian Randle Publishers.